Everyone knows the principle of cruising. On a cruise ship, travellers move at a leisurely pace from one port of call to the next before disembarking. Only selected attractions or towns are visited on site. The entire destination and the surrounding area are not covered, also due to time constraints – some “Must-Sees” are left out accordingly. At the same time, the ship offers all kinds of entertainment, restaurants as well as other travellers to get to know. So the means of transport includes a lot of added value. The route becomes the destination. Sounds like Slow Travel? But it is not!

Slow Travel is the counter-movement to package tours. Cruise ships are the ultimate in package holidays. The contrast is obvious – which is why this article does without a detailed pro-contra list.

Because of its poor image in terms of ecological sustainability, the cruise industry is working on its public image. In the NABU Cruise Ranking 2023, the measures of the shipping companies were put under the microscope.1 Especially smaller cruise operators, such as Hurtigruten and Havila from Norway, are making exemplary progress in environmental and climate protection. The shipping companies in Norway are pioneers in sustainability, as there are political regulations in addition to technical innovations. Among other things, e-fuels (hydrogen), batteries and shore power are used. Synthetic methanol is also being touted as the green fuel of the future. Nevertheless, there are major differences between the fleets of the companies. Older ships in the fleet are hardly ever retrofitted and improvements are almost only carried out on new ships.

Another ray of hope is the EU Green Deal adopted in May, through which the EU aims to become climate-neutral by 2025, which will also have an impact on shipping companies. When using shore power, the ships switch off their propulsion and obtain their energy via shore power connections. Residents around the port are thus exposed to less air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions fall. In Germany, such connections already exist in Kiel, Rostock and Hamburg.

Nevertheless, the NABU report points out that overall emissions from the cruise industry continue to rise. The increase in methane emissions from the use of liquefied petroleum gas is very harmful to the climate. Although liquefied petroleum gas is considered a bridging technology, it is 80 times more harmful to the climate than CO2.2 The main exporter of liquefied petroleum gas is the U.S.A., where environmentally damaging fracking is increasingly used to extract the gas.3

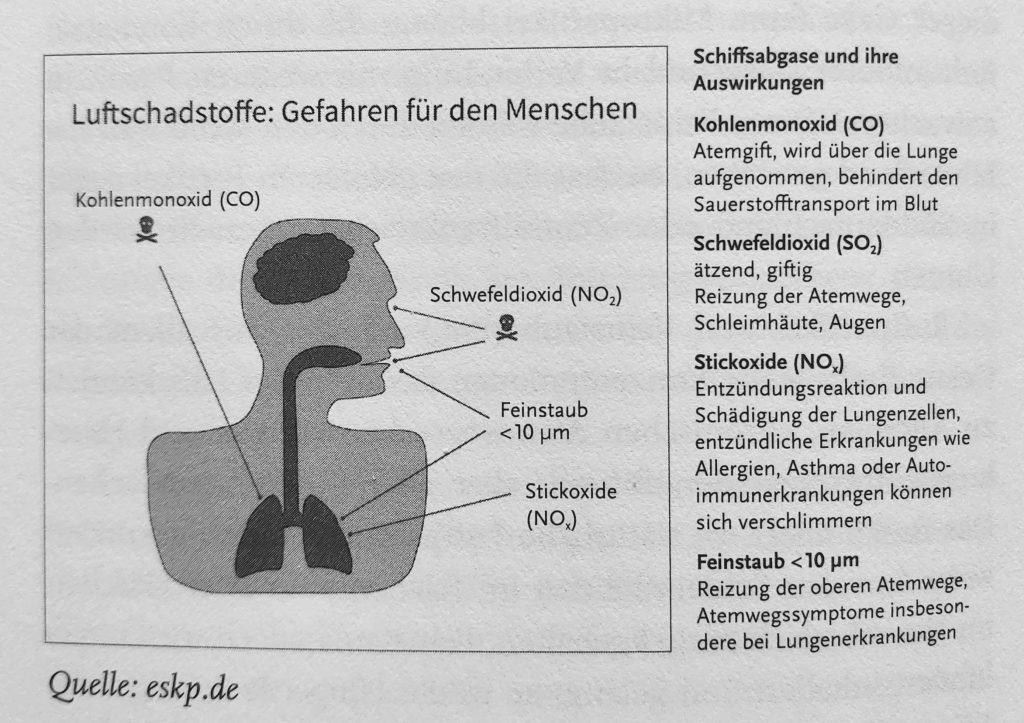

Incidentally, the exhaust gases are also harmful to the cruise passengers themselves. NABU studies as well as television crews from ZDF have repeatedly shown excessively high concentrations of soot and fine dust on the decks of cruise ships, which at 450,000 particles per cubic centimetre were far above the peak values in large cities. Accordingly, passengers are advised against spending long periods on the decks of these ships.4

The fuel and energy requirements as well as the immense pollutant emissions remain one of the most environmentally damaging factors of cruise ships. In the book “Wahnsinn Kreuzfahrt. Gefahr für Natur und Mensch” author Wolfgang Meyer-Hentrich impressively describes the other areas of concern of cruise shipping companies:

Flags of convenience Shipping companies can sail under a flag from another country. In 2018, out of 1,841 ships of German shipping companies operating internationally, only 305 sailed under German flags.5 Without exception, German cruise ships are registered in Malta, Italy, the Bahamas and Bermuda.6Flags of convenience allow shipping companies to avoid taxes and to circumvent German operating, tariff and co-determination rights. In addition to environmental protection regulations, this also includes regulations on safety, maintenance, stability, fire protection and maritime labour law.7 For example, TUI Cruises from Hamburg has registered its entire “Mein Schiff” fleet under the Maltese flag. This means neither minimum wages nor protection against dismissal for the employees, who are allowed to work twelve hours a day. The entire fleet pays only € 50,000 in taxes to Malta – and that with an annual turnover of TUI Cruises of € 650.8 million (2015).8

Exploitation of staff Almost every third person on board a cruise ship is from the Philippines, which amounts to around 250,000 seafarers. Poverty drives people out of their country to earn money abroad. Cruise ships offer coveted jobs. There are many job agencies in Manila that train personnel for ships and then place them as temporary workers with cruise lines.9

However, they receive very low wages on board for a heavy workload. At MSC Cruises, for example, monthly wages in 2016 ranged from € 616 ($ 657) for a kitchen assistant to € 1,170 ($ 1,250) for an assistant bartender.10 That room and board is included is no consolation, as seafarers live on the job and are away from their families for months at a time, thousands of miles away.

For some cruise companies, however, even the well-trained Filipinos are too expensive. They increasingly employ people from developing countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, Madagascar and India. The recruited staff usually have no seafaring experience or training. Actually, the working hours are internationally limited to 72 hours per week and provide for one day off per week (Maritime Labour Convention). However, cruise lines also violate these regulations. For example, 16-hour working days are not uncommon.11

No tipping The majority of cruise ship employees work in the hotel sector (catering and cabin service), so tipping is an issue. On American cruise lines, 15 to 20 % gratuity is automatically added to the bills. On other ships, such as those operated by European cruise lines, a service surcharge of 15 % is added to all guest expenses on board. Often the tips of the bars and restaurants on board are also retained. For a ship with 4,000 passengers, this adds up to about € 263,000 to € 300,000 ($ 280,000 to $ 320,000) in one week.

Unfortunately, hardly any of this huge sum reaches the staff. Many ship operators use this money to pay for cleaning of uniforms, on-board parties or shore excursions. These are expenses that are actually incurred by the employer. Hardly any of the tips and service allowances reach the staff themselves. Author Meyer-Hentrich therefore advises giving the tips directly to the staff. This is the only way to be sure that it reaches the person.12

Noise Sound travels faster underwater than on land and the noise of ship propulsion can be heard for many kilometres. These long-lasting sources of disturbance drive marine life away from their usual areas and prevent them from reproducing. Especially in seals and whales, the sense of hearing can be severely impaired and interfere with their communication with each other. Among other things, this leads to disorientation, which is one explanation for the frequent mass strandings of whales.13

Rubbish A lot of rubbish is generated on cruise ships. Many companies hand in their waste at the ports for disposal; in Rotterdam, for example, it is 80 % of the incoming ships. However, there is no obligation to dispose of the waste ashore. So ships that want to save on disposal costs dump their waste in the sea. This then ends up in the form of rusty barrels or old electrical appliances in the fishermen’s nets. Another factor is the food waste that is “dumped” into the sea by all ships. This can be around 30 tonnes per week, which are thrown away due to hygiene regulations or the intemperate behaviour of passengers. Food scraps are not toxic, but create more fertiliser and algae in the sea.14

Waste water 200 to 300 litres of water are consumed per passenger on a cruise ship every day. For this purpose, the ships desalinate the seawater with energy-intensive treatment plants. After use, it is returned to the sea. Two types of wastewater are produced: the so-called black water, which is usually dirty water from toilet systems. It also contains hormones, drug residues, bacteria and microplastics. The second type of wastewater, grey water, comes from showers, sinks, the kitchen and swimming pools. Although the wastewater flows through onboard sewage treatment plants, residues of the harmful substances still end up in the sea.15

Toxic Cargo and cruise ships use toxic coatings to prevent “fouling” of the hull. This refers to mussels, barnacles and other organisms that grow on the underside of ships. The coatings destroy the organisms and thus reduce fuel consumption because there is less resistance when sailing. However, the highly toxic substances also get into the seawater and thus into the food cycle of the sea creatures.16

Greenwashing The shipping companies are trying to improve their image. For them, more than 9,000 people on board a pleasure ship is no contradiction to sustainability. In the cruise industry, awards and prizes for environmental protection are given not by external, impartial assessors, but by companies that already work with the shipping companies, for example. An objective assessment is not given. The shipping companies also pro-actively develop sustainability measures to prevent rules and bans by politicians. The AIDA Group, for example, issues an annual sustainability report and has assigned so-called environmental officers to look after wastewater, emissions, rubbish and waste reduction on board the ships. These “measures” have their effect – passengers’ consciences are soothed and AIDA’s cruises continue to be well booked. Passengers are also encouraged on cruise ships to make donations for orangutans, rhinos, rainforest protection or other aid projects, which is intended to enhance the image of the companies. As a side effect, the fundraising campaigns distract from the real problems of the cruise itself.17

Mass tourism Finally, it should be mentioned that cruises contribute to over-tourism in many travel destinations worldwide. Small towns, such as Santorini in Greece, Katakolon or Honfleur in France, have lost their charm and become ports of call for cruise ships. The locals live almost exclusively from the ship tourists who transport them to surrounding towns or to nearby sights. The harbour scene is dominated by flying traders offering cheap clothes, sunscreen or plastic products.

The Estonian city of Tallinn offers an attractive harbour, close to Finland and Norway, and features a medieval centre and an almost completely preserved city wall. The old town area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. With only 40,000 inhabitants, around 4.3 million travellers come to the city each year. For the locals, the old town is now a lost zone, completely dominated by tourism.

Similar streams of tourists are pouring into Barcelona, Venice, Dubrovnik and many other cities.18 The locals are suffering from the masses of visitors, once beautiful neighbourhoods have become uninhabitable and the alleys and walls of the old cities are groaning under the weight of too many feet – sometimes there is discussion about whether the over-visited cities should slide onto UNESCO’s list of endangered world heritage sites.

The Caribbean states are also suffering. For example, 200 cruise ships anchor in the harbour of St. John’s, the capital of Antigua and Barbuda, every year with up to 6,000 passengers per ship. On some days in the high season, three to four huge ships are moored in the harbour. The population of the city itself is 25,000.19

Conclusion

Cruises are neither socially nor ecologically sustainable. Despite attempts to change their image and initial measures for more environmental protection, the “floating hotels” can be classified as harmful to the environment and the climate. Some of the staff are not trained and salaries are too low.

Nevertheless, cruises have a strong argument on their side: they are incredibly cheap. And the price is one of the most important arguments for many travellers.

Since not everyone can be expected to put environmental protection first when planning a holiday, much more international restrictions, taxes and rules towards sustainability are needed. This would drive up prices through concrete and effective measures and thus contribute to a decline in cruise travel.

1See https://www.nabu.de/umwelt-und-ressourcen/verkehr/schifffahrt/kreuzschifffahrt/33548.html (10.09.2023)

2See ibid.

3See https://www.nabu.de/umwelt-und-ressourcen/energie/fossile-energien/erdgas/32698.html (10.09.2023)

4See Meyer-Hentrich, Wolfgang (2019): Wahnsinn Kreuzfahrt. Gefahr für Natur und Mensch, p. 111.

5See ibid. p. 54.

6See ibid. p. 57.

7See ibid. p. 55.

8See ibid. p. 57 – 58.

9See ibid. p. 66 – 67.

10See ibid. p. 68.

11See ibid. p. 72 – 73.

12See ibid. p. 77 – 83.

13See ibid. p. 119.

14See ibid. p. 118 – 199.

15See ibid. p. 116 – 117.

16See ibid. p. 115.

17See ibid. p. 123 – 131.

18See ibid. p. 147 – 151.

19See ibid. p. 151 -152.

Article by Anika Neugart.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also like …

Picture: Mstyslav Chernov. Source. License

23 July 2021

Overtourism – The Tourists Go Home and Fuck AirBnB movement

Synchronized with the origin of the Slow Travel trend, a protest movement against mass tourism started. It’s also referred to as “Overtourism”, which marks a harmful excess.